The Historic Journey of Manchester’s Furniture Industry

Manchester has a long and storied history of making fine furniture, reaching its peak in the mid-19th century when 43 separate cabinet shops, factories, and mills were operating in town. Hundreds of local craftsmen were at work, making furniture that was both functional and of museum quality.

Manchester’s national reputation as the maker of fine furniture had humble beginnings. In 176l, Moses Dodge, a native of Beverly, moved to Manchester and opened a shop at 21 School Street. He was known as a “joiner”, making everyday furniture for residents. Soon, furniture-making replaced fishing, farming, and privateering as the town’s source of income.

Dodge millManchester furniture proved immensely popular, especially in the South. This was both a blessing and a curse, for the Union Navy blockaded the southern ports of entry when the Civil War erupted. This loss of market and the departure of Manchester’s workforce to join the Union Forces started the decline of the once-thriving furniture industry in town.

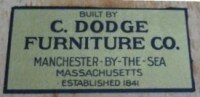

Two notable exceptions were the shops of Charles Lee and the Dodge family. Lee was renowned for making ornately carved beds which continued to be much sought after in the South following the war. And the Dodge Company remained in operation until 1965, enjoying a much-deserved reputation for its fine reproductions of period furniture.

Apprentices & Carvers

With cabinet shops springing up all over town, young apprentices were in much demand. If a boy didn’t want to farm or go to sea as his grandfather had, he could always apprentice himself to a cabinetmaking friend of the family.

A shop might house the master craftsman, an apprentice or two, and a journeyman. In the 1830s, a journeyman made a dollar a day, and an apprentice might earn an annual salary of $120 in his first year and $130 in the second. To encourage production, apprentices were given a “stint” or a set of tasks to be performed in a given number of days, and any time gained was valued at 20 or 30 cents per day. “In the fall and winter, lights would often be seen before dawn and as late as 11 or midnight. One dozen lamps with whale oil filled the shops with smoke”.

At, the pinnacle of the cabinetmaking pyramid stood the carvers. The elaborate carving, a hallmark of Manchester’s Victorian-style furniture, was usually done in a third-floor workroom with better light and relative peace and quiet. Isaac Marshall recalls watching a carver working on a piano at his father’s furniture factory in 1875. “I was fascinated in seeing flowers, birds, and vines taking form out of wood blocks under the skill of the carver, George Brown.” The piano was to be Isaac’s 10th birthday present and is part of the Museum’s permanent collection.

One of Manchester’s most celebrated carvers was Andre Ruffin, who worked in the shop of Rufus Stanley. An excellent example of his skill is the fancy side chair on display. Andre was only 17 years of age when he executed the intricate carving!

John Perry Allen – “The King of Furniture Makers”

Arguably the most important cabinetmaker in Manchester was John Perry Allen. After serving as an apprentice to Caleb Knowlton in the early 1800s, Allen opened his shop on Forest Street in 1818, then moved to 10 Union Street, the site of the Manchester Historical Museum.

As his business grew, Allen bought the town’s original grist mill where the Sawmill Brook empties into the harbor – where the Seaside No. 1 firehouse stands today. Allen was especially enterprising, once taking two of his bureaus aboard a fishing boat to Boston, selling them for $20.

With his invention of New England’s first steam-powered veneering saw, JP Allen began to produce some of the most fashionable furniture of its time, expanding his markets to New York, New Orleans, and Boston. His revolutionary saw could slice a 4 thick block of mahogany into 100 sheets of perfect veneer. Unfortunately, his invention was patented by a competitor.

Allen also had the misfortune of being plagued by fires – four times in four locations! He lost his home and mill on Saw Mill Brook in the Great Fire of 1836. In 1845 his mill at Days Creek (near Masconomo Park) burned down; in 1852, another mill at the end of Elm Street succumbed to a boiler explosion. And in 1856, another fire damaged his property at the corner of Central and Elm.

His bad luck notwithstanding, Allen had established a national reputation. At his death in 1875, the Philadelphia Trade News wrote that JP Allen was “perhaps as well if not better known than any members of the trade”.

“The Great Fire of 1836”

When workmen left the veneering mill of John Perry Allen on Friday, August 25, 1836, all was in order. Great stacks of wood from Maine and Honduras filled the mill, some ready to be sliced into perfectly cut veneer strips by Mr. Allen’s revolutionary new saw. And typical of all such shops in town, the building was filled with combustibles – sawdust, solvents, kerosene, and lots of wood!

Around 3:00 AM that Sunday, a spark smoldering for hours in the boiler room ignited a pile of mahogany dust. Within a matter of minutes, Allen’s mill was fully engulfed! An easterly wind then drove the fire across Sawmill Brook, torching scores of other shops, outbuildings, stables, and homes fronting Central Street and destroying the wooden bridge that linked Central and Bridge Streets. Losses totaled close to $100,000; $60,000 was absorbed by Allen alone!

When the church bell sounded the alarm, volunteers arrived on the scene with the town’s one piece of equipment – the hand-pumper Torrent. This unique apparatus had been designed and built in 1832 by another of Manchester’s many cabinet makers, Colonel Ebenezer Tappan, Jr., whose shop was not far from the scene of devastation.

To help fight the fire, aid came from neighboring towns. At the next Town Meeting, a local tavern keeper presented a bill for the wine, rum, and brandy served to help quench the thirst of all those volunteers!

Although the “Great Fire of 1836″ destroyed a good portion of downtown Manchester, the Torrent was credited with helping contain the conflagration and remained in service until 1885, when a horse-drawn steam pumper replaced it. To house this apparatus, the town built its first official Fire House – Seaside No. 1 – ironically on the very site of John Perry Allen’s ill-fated veneering mill!

Rust and Marshall – Furniture, Pianos, and Organs

Just as John Perry Allen moved his cabinet shops all over town, so did one of his major competitors, Rust and Marshall. Their first factory was built on the very site of Allen’s mill that was leveled by the “Great Fire of 1836″. Like most of Manchester’s furniture giants, Nehemiah Marshall began his career as an apprentice, learning his trade with Alfred Jewett, who operated a chair factory on Knight’s Wharf (today still standing as the brick building at Peele House Square). After several years as Jewett’s partner, Marshall left to form a new business with William C. Rust, making furniture for the wholesale market on a large scale.

Unfortunately, their imposing three-story factory suffered the same fate as Allen’s mill, succumbing to fire in 1871. They relocated to Elm Street, where they built a large steam-powered mill. The business prospered for a few more years, but the depression of the 1870s, combined with competition from furniture makers in the mid-west, forced the partners to explore new options, including building cases for upright pianos and parlor organs (they bought out the Manning Organ Company of Rockport in the process). Both ventures failed, and by 1886 Rust and Marshall were finished.

On a happier note, Isaac Marshall, son of Nehemiah, became one of Manchester’s most prominent citizens. He was a world traveler, author, and the first editor of the town’s newspaper, the Manchester Cricket. He was also a major benefactor of the Manchester Historical Museum, donating many family pieces of furniture made in his father’s factory.

Charles Lee and the Southern Connection

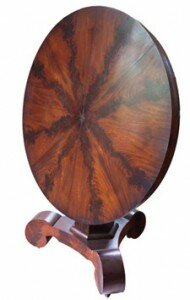

The story of Charles Lee is a fascinating one. Born in Manchester in 1817, Lee was an apprentice with John Perry Allen, married Allen’s daughter, and eventually started his own furniture business in a steam-powered factory on Elm Street. By 1860, Lee employed 18 workmen to manufacture mahogany, rosewood, and pine beds, most of which were shipped to the South, where their Rococo Revival design was especially popular. Today Lee’s beds still command top dollar, appearing at auction for as much as $10,000!

Lee’s business thrived until the Civil War when the Union Navy blockaded the southern ports. Many of Lee’s workers enlisted in the Army, and Lee himself served for three years. When peace was restored, and trade resumed, Lee was back in business. In 1867, he shipped 155 cases of bed components to 12 dealers in New Orleans. There the parts were assembled, and local carvers embellished the bed posts with Southern motifs.

All of Lee’s beds were stamped “C. Lee”, but not until 1994 was it learned that “C. Lee” was Charles Lee of Manchester. For years it was thought that the beds had been made in the South and that “C. Lee” was perhaps a “free man of color” who worked for Prudent Mallard, a master craftsman in New Orleans who specialized in furniture made of mahogany and rosewood, the same materials as Lee. To add to the confusion, it is also possible that Mallard’s carvers were the ones who embellished Lee’s beds. It was not until 1994 that Charles Lee was identified as the mysterious “C. Lee”; photographs in the Manchester Historical Museum helped identify his maker’s mark.

The Lee factory shut down in 1868 as competition from Midwestern furniture makers eliminated all but the largest local cabinetmakers.

The Dodge Dynasty – Early Years

No name is better known for Manchester furniture than that of the Dodge family. They started the local industry in 1761 and finished it in 1965. Moses Dodge pioneered, opening his shop at 21 School Street in 1761. One of his sons, Cyrus, apprenticed with John Perry Allen in 1830 and eleven years later had his own business specializing in fancy carved mahogany parlor chairs. In the first year, 1,400 chairs were produced in what today would be called the Early Victorian Style. Dodge called them “French Chairs”, and workmen earned $14 for each dozen produced. By 1847, the business flourished, and Cyrus built a new steam-powered mill between North Street and Desmond Avenue.

Although the Civil War contributed to the demise of most of Manchester’s furniture industry, a few shops did survive, most notably the Dodge Company. The 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia sparked a national re-interest in Colonial furniture, and Dodge was quick to capitalize on this trend, producing high-quality reproductions using the designs and patterns produced by Moses Dodge back in the 18th century.

Cyrus Melville Dodge, John Marshall Dodge, and Charles Coes Dodge—sons of Cyrus, took over control of the company in the late 1870s, enlarged the factory, and expanded production to more varied seating furniture, gradually shifting from eclectic Victorian to Colonial revival.

The Dodge Dynasty – “The Good Old Fashioned Way”

By the end of the 19th century, the character of little Manchester began to change dramatically as it evolved into a thriving summer colony catering to the rich and famous from across the country. And while Dodge rarely advertised, this new clientele was eager to purchase his highly regarded furniture for their homes and as coveted wedding gifts. In addition, many major stores, including the prestigious Paine Furniture Company in Boston, featured various pieces with the Dodge label.

In 1926 nephew Chares E. Dodge took over the business and continued to focus on producing high-quality hand-made reproductions of early American furniture. In one interview, Dodge reported he was “working on a set of chairs for the Governor’s Palace in Williamsburg, working from patterns handed down in the family from the period (Revolutionary War era)”.

In 1956 the business, still making furniture “the good old fashioned way”, consisted of just three employees, each more than 50 years of age. One was eighty, and Charlie Dodge, who never made a stick of furniture himself, was 67. But the old shop kept chugging along, never compromising its commitment to excellence. After 118 years of operation, the doors finally closed in 1965 upon the death of Charlie Dodge.

Dodge glassed case any artifacts, records, ledgers, drawings, and patterns were acquired by the Winterthur Museum in Delaware before the mill between North Street and Desmond Avenue was razed. In its place now stands an apartment complex. But the legacy of the Dodge Company will live forever as an example of Manchester’s heritage in the manufacture of fine furniture.

Making Fine Furniture – Today’s Master Craftsmen

While there are no more furniture factories or mills in Manchester, the tradition established by John Perry Allen and Charles Lee and the Dodge family is alive and well in the workshops of at least two local artisans.

Fred Rossi, for example, has a thriving business creating custom pieces in his home workshop on Highwood Road. He started Rossi Custom Woodwork in 2001 and today has more than enough business to justify what might have seemed a risky venture thirteen years ago. “From the type of wood to hardware and finishes, every piece is designed and built from scratch by Rossi, built for one person with one specific place in mind”, according to an article in the 2013 Winter edition of CAPE ANN – North of Boston Life magazine. “I like the organic process of designing from scratch”, Rossi said. Fred recently donated a custom-made contemporary table to the Manchester Historical Museum, which will become a welcome part of our permanent collection. It is on display in this exhibit.

Former Manchester dentist Jim Bacsik builds furniture as a hobby rather than for his livelihood. Jim moved to Manchester in 1974, residing in a historic house on Union Street. In the mid-1900s, Jim began to build a few pieces of “period” furniture to help furnish his 1842 home. “I took several classes with Gene Landon, a famous maker of high-quality 18th-century reproductions. He was particularly interested in the Philadelphia High Style, and I came to share his appreciation for the skill of the early cabinet makers. I also took several classes with Allen Breed, an expert on the Newport Style.” A look at some of Jim’s reproductions shows he learned his lessons very well! Now retired and living in West Gloucester, Jim continues to create pieces based on the High Style but with a few contemporary variations.

Manchester Cabinetmakers

This list is compiled from several sources by Sally Gibson, who worked in the MHM archives in the 1980s. It is in chronological order, and the dates are the approximate working years in Manchester in the cabinetmaking business.

- Moses Dodge, working 1761-1776

- Caleb Knowlton 1800-1814

- John Dodge 1772-1831

- John Perry Allen 1814-1875

- Ebenezer Tappan Sr.

- Forster Allen 1803-1839

- Larkin Woodbury

- Ebenezer Tappan Jr. – 1875

- Albert E. Low

- Rufus W. Long, succeeded by Long and Danforth

- Long, Allen and Co.

- Kelham & Fitz

- Bingham & Co.

- Cyrus Dodge 1814-1887

- Fitz & Kitfield

- Leach, Annable & Co.

- Henry F. Lee

- Isaac Allen 1805-1879

- John Felker

- Jeremiah Danforth

- Proctor & Godsoe

- George Marble

- Frederick Burnham

- Simon Farris

- John C. Long & Co.

- G. O. Boardman

- H. P. and S.P. Allen

- Andrew Lee ( son of Andrew)

- Samuel Parsons

- Andre Lee ( son of John)

- Allen & Ames

- Isaac S. day

- William Hoyt

- Abram Rowe

- John C. Webb

- Severance & Jewett

- Jewett & Marshall

- A.S. and G.W. Jewett

- William Johnson

- Claudius B. Hoyt

- Julius Rabardy

Second Half of 19th Century

- Warren C Dane

- Felker & Cheever

- Hanson, Morgan & Co.

- E. S Vennard

- William Wheaton

- Charles Lee

- John C. Peabody

- Isaac Ayers

- Crombie & Morgan

- John M Dodge

- Rufus Stanley

- Charles C. Dodge 1853-1826

- William Decker

- Watson, Taylor & Co.

- Rust & Marshall

- Lewis Morgan

- Samuel Wheaton

- Charles E. Dodge

Early Carvers

- George Taylor

- William Lindsey

- George E. lee

- Alexander Stewart

- Larkin W. Story

- Andre Ruffin

- Luther F. Allen

- Andrew J. Crowell

- Andre Lee

- Robert Thornton

- Rufus Long

- William Webb

- Charles Goldsmith

- Samuel Crombie

- Ivory Brown

- John L Eaton

- Jacob Allen

📎 Related Articles

1. The Largest Empires in History: A Profound Legacy

2. Exploring the Opulence: America’s Gilded Age Summer Cottages

3. Manchester’s Historic Seaside No. 1 Firehouse

4. Trask House: Preserving History in Every Corner

5. The Riveting Timeline of Manchester-by-the-Sea